By Bloomberg News

Mar 6, 2014 5:00 PM ET

China’s leaders want to lift the gray blanket of deadly smog that often chokes Beijing’s residents by shifting power plants to the less populated western part of the country inhabited by minorities. That’s turning into a nightmare for Ani Yetahon who lives in Oriliq, a village about 1,800 miles from the capital where some residents still walk to the well for their water.

Ever since a $2.1 billion plant that converts coal into natural gas began operating in August on a hill above his village, the 37-year-old ex-policeman and his family have suffered a burning sensation in their throats that keeps them awake at night. So have his fellow villagers, who also complain of dizziness and repeated colds.

After five months of watching clouds of smoke belching into the air from a red-and-white striped smokestack, they’d had enough. On a mid-January morning, more than 200 people dragged makeshift wooden barricades across the snow and blocked the road leading to the plant. They stayed for two days, in temperatures that dipped as low as minus 20 degrees Celsius (minus 4 degrees Fahrenheit). Their demand: shut down the installation that was making them and their children ill.

Nothing changed.

“They don’t care if our children get sick or how much the pollution is affecting our village,” said Yetahon, a stocky man dressed in a gray sweater and brown leather jacket, whose village is near the Kazakhstan border. When senior police officers asked him for the names of those who organized the protest, Yetahon said he turned in his uniform and quit.

Under Pressure

Yetahon, like most people in his village, is a Uighur who lives in the restive Xinjiang province, home to 10 million mostly Muslim, Turkic-speaking members of this ethnic minority. They face restrictions on their movement and religious worship.

“If we do nothing, then we live with the pollution and the damage to our health,” he said a week after the demonstration. “If we stand up and protest, that also brings hardship.”

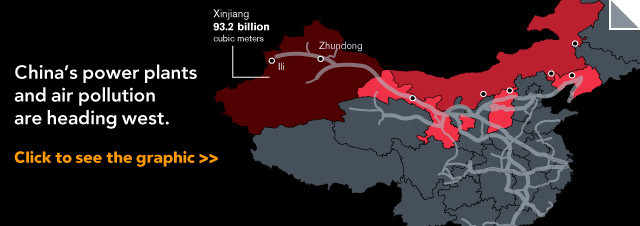

Under pressure from an increasingly vocal middle class incensed by record levels of pollution, China in September said it won’t approve the construction of new coal-fired power plants around eastern cities. The upshot is an outsourcing of pollution west and north to provinces including Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia that are far from the glare of the media and where dissent is more tightly controlled.

Pollution Deaths

A March 1 attack by knife-wielding assailants that killed 29 people and injured more than 100 in southwest China was blamed by officials on separatist forces from Xinjiang. President Xi Jinping ordered a crackdown on terrorist activities, while opposing any backlash against ethnic minorities, the state-run Xinhua News Agency reported.

Xi said last week pollution was Beijing’s most prominent challenge and foreign companies and residents have joined the chorus of criticism by local residents. The leadership said it plans to shutter 50,000 small coal-fired furnaces this year and reduce air pollution that results in as many as half a million premature deaths each year nationwide, according to an article in the London-based Lancet medical journal co-authored by China’s former Health Minister Chen Zhu.

At the same time, China is currently building as many as 70 coal-fired power plants in the western part of the country to meet the nation’s energy needs, according to Xizhou Zhou, Director of China Energy at IHS Inc., an Englewood, Colorado-based consulting company. In addition, the government has planned 30 coal-to-gas plants, some of which are already operational like the one that sparked protests in Yetahon’s village. Of those, at least 20 will be built in Xinjiang, according to a study by Ding Yanjun, an associate professor in Tsinghua University’s Department of Thermal Engineering.

‘People Die’

“In the short term, these projects will help the coastal cities a little bit, but in the long term this is really, really bad for the environment,” said Chi-Jen Yang, a research scientist at Duke University in North Carolina who focuses on energy policy. “It will help the smog on the coast and move the pollution to western provinces.”

Aypujan Niyaz, a 34-year-old chemical factory worker who lives in Chuluqay, a few minutes’ drive from Yetahon’s village, puts it more bluntly: “In the east it is Chinese, that’s the difference,” he said. “Here it’s over 90 percent minorities -- Uighurs, Kazakhs. If there’s pollution they will just say, ’Oh well, there’s pollution.’ If people die they will just say, ’Oh well, people die.'”

Climate Change

Comments by Chinese officials and policy documents point to Xinjiang’s coal resources as crucial to powering the country’s economic growth and driving development as part of the country’s “Go West” investment policy. Xinjiang’s economy is less than one third the size of Hebei, which is China’s most polluted province and surrounds Beijing.

Xinjiang should become a strategic energy base and its resources should be developed, Vice Premier Zhang Gaoli said at a September meeting on Xinjiang attended by members of the Politburo Standing Committee, China’s most powerful ruling body.

The Ministry of Environmental Protection, the National Development and Reform Commission, which approves energy projects, and the Communist Party Committee of Xinjiang didn’t reply to questions sent by fax.

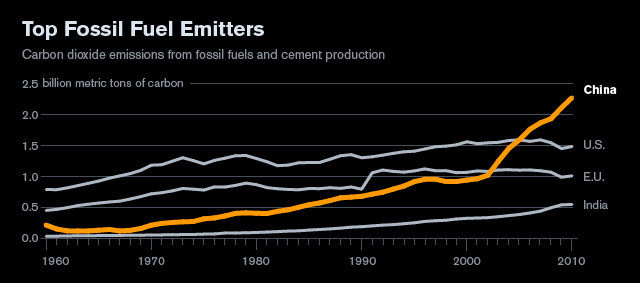

China says it needs to continue rapid economic development to ensure all its people benefit. Responsibility for solving climate change should be shouldered primarily by the U.S. and European nations since they produced the bulk of emissions that cause global warming during their industrialization, China said in a 2011 white paper. Per capita energy consumption in China was less than a third of the U.S. in 2011 and about two thirds of the European Union, according to World Bank data.

Globally Resilient

China’s continued embrace of coal shows how, despite a concerted campaign by environmentalists and public health experts to stanch its use, coal is proving globally resilient.

Even in Europe, where pushing renewable energy has been a priority of the EU, utilities are expanding open-pit mines that produce a cheap, dirty-burning coal known as lignite to turn back sharply rising electricity prices. In the U.S., a spike in natural gas prices has some analysts projecting that utility coal use could supply 40 percent of power production within three years after slumping to a record low of 37 percent in 2012.

Clean Energy

Even though China is currently the top global investor in clean energy, it will still be reliant on coal for most of its electricity in 2030 -- by when its power needs will have more than doubled, according to a report by Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Already the world’s biggest consumer of coal and biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, that means China will add the equivalent of the total installed power capacity of the U.K. each year.

Much of China’s new power generation capacity will be in Xinjiang where there are plans to add a total of 48.9 gigawatts of capacity, according to IHS data. That’s more than double any other province.

Electricity produced in Xinjiang began coursing eastward in late January with the inauguration of the world’s longest ultra-high voltage line, which starts in the city of Hami, home to half a million people. A front-page article in the government-controlled Hami Daily in 2012 extolled the power plans: “Sending Xinjiang’s Power East Awakens a Sea of Sleeping Coal,” read the headline. China is investing as much as half a trillion dollars in power lines to carry electricity to the east.

Spoiled Dates

The city, in eastern Xinjiang, has long been known for its sweet, golden melons that for centuries refreshed travelers on the old Silk Road. Now, towering smokestacks and dormitories that house power plant construction workers interrupt the horizon where the brown sands of the Gobi Desert meet a shimmering blue sky.

A few kilometers from a coal-fired plant built by a unit of state-owned Shenhua Group Corp. that opened in 2011, villagers in Huicheng on the outskirts of Hami say pollution is affecting their livelihoods. Standing in the garden of his home, Ibrahim Rozi rolls a dust-covered date between his fingers. The pollution has caused them to shrivel and the dates fetch only a third of the price they used to, he said.

“Their color isn’t good,” said Rozi, 34, who describes how a thin layer of black soot covers the snow in winter. “The pollution has gotten much more serious.”

Police Presence

In a neighboring village, Li Zhihua, a 21-year-old Han woman, remembers when the fields surrounding the plant were filled with “some of the sweetest” melons in China. She says the melons are smaller and have lost their taste because of the pollution and the fact the installation devours scarce water resources.

“When I was growing up here, Hami melons were so sweet,” Li said, sitting near the doorway that leads into the courtyard of the family home. “In the past few years they barely have any flavor.”

Shenhua didn’t respond to questions sent by fax.

Hawkers selling round sesame-covered breads line the two-lane road that runs through the village. Butchers wielding hatchets lop off chunks of lamb from carcasses hanging from trees.

The other ubiquitous presence on Xinjiang’s roads is the police. Drivers are regularly stopped and their cars searched at checkpoints.

Ethnic Tensions

Two Bloomberg News reporters speaking to a family in late January, in their home across the road from the Hami plant, were interrupted when three police officers entered the courtyard as they talked to two women. The reporters were asked to show their ID documents and one policeman went inside. Officers then waited in their patrol car until the reporters had left.

Xinjiang has long been a cauldron of ethnic tensions and the Chinese government has pointed to the province as a source of terrorism and separatism. Authorities blamed Uighur militants after a vehicle rammed into a crowd in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in October, killing two bystanders and three people in the car.

While about 92 percent of China’s 1.3 billion population is ethnic Han, more than 45 percent of Xinjiang’s 22 million people are Uighurs. Riots in 2009 in Urumqi, the provincial capital, killed 197 people and injured more than 1,700, according to state-run media.

Residents who attended the gas plant protest in Oriliq, the village where Yetahon lives near the Kazakhstan border, said police threatened them with arrest and party cadres warned that their demonstration could be hijacked by separatists. The police department in Yining county didn’t respond to questions sent by fax.

‘Tremendous Risk’

“There’s a tremendous risk especially for the largely Muslim population,” said Judith Shapiro, a professor at American University in Washington D.C. and author of “China’s Environmental Challenges.” “If there are environmental protests in an area which is heavily minority populated there is a tremendous risk they will be tarred as separatists or even terrorists.”

In Chuluqay, a few minutes’ drive from Yetahon’s village, an elderly woman lies on a steel-framed bed in a one-room clinic. She’s been hooked up to an intravenous drip for two days. She’s the mother of Niyaz, the chemical factory worker, who has a computer science degree and is one of the few people from the area to have attended college.

Kneeling on a carpet in his home and drinking tea as his younger sister stoked a coal-fired stove, Niyaz explained that his mother was being treated for a sore throat and headaches caused by fumes from the coal-to-gas plant. He is worried that the pollution will become like the “London fog,” a reference to the lethal smog that engulfed the city in 1952. It killed as many as 12,000 people and gave impetus to the environmental movement in the U.K.

Respiratory Problems

In the pediatric ward of Yining County People’s Hospital, about eight miles (13 kilometers) from Niyaz’s village, doctors say they have seen a marked increase in the past few months in the number of babies suffering from respiratory ailments.

“This year there are many more infants coming in with colds that develop into pneumonia,” said Gulsana, a doctor who sat behind a computer in the ward where Mickey and Minnie Mouse stickers cover the walls. “I think it’s because of the Kingho plant,” she said, referring to China Kingho Energy Group, which operates the installation.

Kingho officials didn’t reply to questions sent by fax.

No Rabbits

In Oriliq, Yetahon is among a group of farmers chatting and smoking outside the convenience store as they kill time in the winter when their fields are covered in snow. One recalls a woman fainting from the fumes spewing from the plant. Another says his children can’t concentrate at school. A third says the rabbits that used to scamper across the surrounding hills have disappeared.

Shortly after the plant began operating, Yetahon wrote a report to his superiors about the effects of the pollution. He said senior police officers promised to investigate but never did.

Villagers also complained that they aren’t benefiting much from the plant, which has imported workers from outside Xinjiang. Uighur residents who have applied for jobs said they were offered menial work like taking out the trash or cleaning toilets.

Sitting in his home later, Yetahon recalls the two-day protest over a meal of steamed buns, pickled vegetables and ginger tea in a room where colorful tapestries hang on the walls. A part-time farmer, he plans to grow corn and wheat full time now that he’s quit his job as a policeman. He doesn’t know if he can earn a living this way.

Officials ended the protest by promising to cut pollution from the plant and ensure it installs equipment to reduce emissions by the end of March, villagers said.

Yetahon isn’t hopeful.

“They’re not really going to shut down the plant,” he said, as his two children, age five and nine, rolled around on the floor playing with his mobile phone. “They’ve already spent too much money building it.”