Image:

Body:

IN AN ominous sign of the fate awaiting one of China’s best-known Uighur intellectuals, security officials in the far western region of Xinjiang issued a statement on January 25, accusing him of separatism and inciting ethnic hatred.

The statement provides the first concrete indication that the scholar, Ilham Tohti, an economics professor in Beijing, could face a long prison term for his advocacy on behalf of Uighurs, the Turkic-speaking Muslim minority whose uneasy coexistence with the Chinese authorities has grown increasingly violent.

Tohti has been held incommunicado since January 15, when police officers escorted him from his apartment on the campus of Minzu University of China.

The news that he is likely to face charges of separatism comes at a time of intensifying bloodshed in Xinjiang despite a growing security presence by Chinese soldiers and paramilitary police officers. On January 24, 12 people were killed in a town not far from Xinjiang’s border with Kyrgyzstan. A state-run news portal said that the police shot and killed six people in Aksu Prefecture, and that six others died in what were described as three explosions.

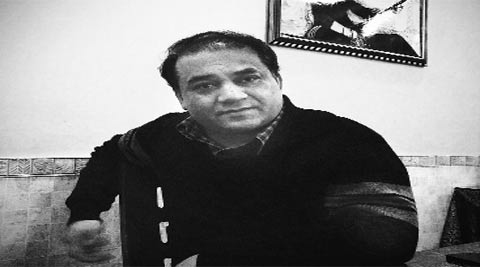

A vocal advocate for China’s Uighur minority, Tohti, 44, was the rare public figure willing to speak to foreign news media about the Chinese government’s policies in the vast region that borders several Central Asian countries.

He was also the target of frequent harassment by the Chinese authorities, especially after he helped establish Uighurbiz.net, a website for news and commentary on Uighur issues.

Censors blocked the site in 2009 after ethnic violence in Urumqi, the regional capital, claimed nearly 200 lives.

Since then, several people involved with the website have been given long jail terms.

In the statement issued on Saturday night on its microblog account, the Urumqi Bureau of State Security accused Tohti of inciting violence against the Chinese authorities and recruiting people to join a movement for an independent East Turkestan nation.

“Ilham Tohti exploited his status as a teacher to recruit, entice and coerce people to form gangs, and to collude with ‘East Turkestan’ leaders in assigning people to go abroad to join in separatist activities,” the statement said.

Analysts outside China have long questioned the official narrative about the violence in Xinjiang, including allegations that the East Turkestan Islamic Movement was behind much of the bloodshed.

Tohti was among those who played down the strength and size of the organisation, saying that many of the clashes involving Uighurs and the police were rooted in the daily frustrations experienced by Uighurs disenfranchised by repressive policies and uneven economic development. In interviews with The New York Times, Tohti condemned the growing violence, but called on Beijing to re-examine its policies in the region.

Over the past year, confrontations have been occurring with greater frequency, alarming Chinese leaders and prompting heavier security in the strategically important and energy-rich region. Beijing recently announced that it was doubling Xinjiang’s public security budget, with one regional official vowing “no mercy for terrorists”.

Exile groups like the World Uyghur Congress attribute many recent Uighur deaths to aggressive policing tactics, and say that many of those killed and described as “terrorists” were carrying only knives or farming tools.

Over the past two months, nearly three dozen Uighurs in southern Xinjiang have been shot and killed by police, including three young men killed January 15 outside a police station in Aksu Prefecture.

Security agents opened fire after the men had been denied entry to a local police station, according to Radio Free Asia. The report quoted local police officials as saying the men were carrying sickles and described them as “separatists”.

Over the years, Tohti had become inured to the constant surveillance and the occasional detention, including forced “vacations” during which minders would escort him to a hotel outside Beijing for days or weeks.

In November, as he and his family drove through the university gates, he said, a car driven by plainclothes security agents rammed into his vehicle, and the men threatened to kill his wife and children if he did not stop speaking to the foreign news media. The episode occurred days after a deadly attack near Tiananmen Square in which a Uighur man drove a vehicle along a sidewalk, striking numerous pedestrians and killing two. A security official later blamed the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, although he provided no evidence of the group’s involvement.

During the raid of Tohti’s apartment this month, security agents carted off documents, computers and cellphones while his wife and two young children looked on. At least six of his students were also taken into custody, said his wife, Guzaili Nu’er.

Tohti was aware that his freedom was tenuous. In one interview in 2010, he expressed resignation over his fate. “If things here don’t change as quickly as I’d like, sooner or later I will be doomed,” he said. “Perhaps I will be sent to hell, but I don’t care because in some ways I am already there.”