Image:

Link:

Body:

My name is Mutellip Imin. I am from Lop County in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region of China. From July 15 to October 1, 2013, I was incarcerated by the Xinjiang police in three different hotels, without any legal procedures.

On the evening of July 14, 2013, I arrived at Capital International Airdrome in Beijing and went to the ticket counter to check in for my flight from Beijing to Istanbul. The ticket agent told me to wait and left with my passport. I was waiting for an hour until I was taken to the Airdrome police station where my backpack and PC were inspected. The customs agents told me that there were no suspicious items found in my belongings and that I would not miss my flight to Istanbul. I was, however, retained at the police station until two police officers came to inform me that I was wanted by the police in Xinjiang.

My passport, cell phone, Turkish residency permit, and my Turkish language proficiency certificate were all taken by the police, and I was handcuffed and brought to the repatriate center near the Airdrome. On the way, I begged the officers to let me contact my loved ones. They refused even to send my girlfriend, Atikem, a message that I was incarcerated. They told me I would be able to contact my relatives when I got back to Xinjiang.

After I was booked at the repatriate center, I was locked in a small room and put under surveillance. I was woken twice in the night, the first time to be fingerprinted and the second time to be taken to meet with some people from Xinjiang. They had my belongings in a mess on the floor and were reading a letter to my girlfriend. There was a Uighur among them.

“Are you doing this in accordance with the law?” I asked him.

“Yes, we are doing this in accordance with the law,” he said.

“With what law?”

“The law of the People’s Republic of China.”

“What law did I break?”

“Someone will tell you when you get back to Xinjiang.”

On July 15, at around 6 am, we set off by plane on our way to Urumqi. I was accompanied by two Han Chinese and a Uighur. They did not give their names or tell me what roles they had in the case. I assumed they were police.

It was about 1:30 in the afternoon when we arrived in Urumqi. I was brought to a room at the Ili Hotel(伊犁大酒店), and the three men told me that if I was on my best behavior when the police chief was there, this would all soon be over. I saw them write, “Xinjiang Public Security Police Penal Spy, Second Detachment.” By their writing, I determined that they were from Xinjiang.

Later, the police chief came into the room with a stack of several hundred pages he said were about my case and distributed them among the three men. Then they forced me to give them the passwords of my cell phone, PC, email, WeChat, Twitter, Facebook, QQ, etc. They even demanded the administrator password of Uighur Online (www.uighurbiz.net) website which Mr. Ilham Tohti had created to bring harmony between Uighurs and Han Chinese. As the password had changed when I was outside of China, I did not know the new password. They did not believe me and would continue to ask me for the password several times a day.

Starting on July 16, they took notes. They asked me mainly about my relationship with Ilham Tohti, how I knew him, and Uighuronline. I told them that I had attended his classes and helped him translate some news about Xinjiang from Uighur and English to Chinese. I wrote articles about making the Noruz festival a legal holiday, Han Chinese students living in Xinjiang, the incident on April 23 when a number of Uighurs were killed, and Uighur education in Xinjiang. I also helped manage the Facebook and Twitter accounts of the newer version of Uighuronline: Uighurbiz.net.

In 2010, I started dating Atikem. We attended classes and lectures together. On her Sina MicroBlog, named Uyghuray, she wrote about her failed attempts to get a Chinese passport.

During my military service, I made an acquaintanceship with Parhat Xalmurat who was a graduate student at Minzu University of China and wrote his graduate thesis on bilingual education. Parhat was a Minkaohan (a Uighur student who is educated as a Han Chinese beginning in childhood). I, therefore, helped him with his Uighur language skills. He had a good relationship with Ilham Tohti. He joined the Uighuronline translation group as a volunteer.

While attending Ilham Tohti’s classes, I met a number of other Uighur scholars.

In the room at the Ili Hotel in July of 2013, I told the police all about my acquaintanceships with Uighur and Han Chinese people.

The police chief asked me, “Do you know anybody working for any overseas organizations?”

“No,” I said.

“And what about for the East Turkistan organization in Turkey?”

“No, I’ve just heard of a few names in the media, but I don’t have any connection with them.”

On the morning of July 18, I signed my name and gave my fingerprints. The officers told me that they wanted me to wait for a few days while my case was being discussed. In that hotel room, I was under 24-hour surveillance until the next day, but I was regularly interrogated and remained confined in there until July 31 when I was taken to the Snowlotus Hotel(雪莲精品酒店) where I was again put under 24-hour surveillance. They asked me questions about my applying for a scholarship in Turkey.

I still wasn’t able to contact any friends or family. By this time, I was experiencing mood swings.

Finally, on August 10, I was given a cell phone and allowed to call my loved ones. They dialed my girlfriend’s number, put the phone on speaker, and set the phone down on a chair. I felt great tension when she asked me whether there were police officers around me. This feeling was exacerbated after I got off the phone and the police told me to call her back and tell her that I had actually been free and with friends for a long time.

We soon learned that someone in Beijing had informed my family that I was incarcerated. The police then became angry and withdrew their permission to let me talk to my family.

On August 11, they said I would be able to go free in a few days. I waited and waited. August 30, the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances, came and went. On August 31, the police made me write a statement of my “wrongdoings.”

On September 3, three men with video recording equipment came. They looked at the statement I had written and then added the following: “My eyes were blinded by Ilham Tohti, and I defied my countries religious policy and played a very bad role on the Internet. Helping to maintain and develop Uighuronline was my essential fault. I also acted badly by broadcasting words that threaten the harmony among groups of people in China.” I was made to sign and fingerprint this statement. I was then forced to read it in Uyghur and in Chinese while they video recorded me. Then, they had me swear before the Chinese flag: “By this corrective measure, I will abide by the law…” I raised objections, but they threatened to send me to jail for a year or two if I did not cooperate.

After the recording, they told me I would be able to go back to my hometown of Hotan around September 7 or 8 after the Euro-Asian Exhibition and that I could fly to Turkey around the 15th of September. On September 10, they told me I still had to wait, and I would be let go around October 1. They said I could call my family but instructed me to lie to them by saying I was actually in Turkey. I was to tell them that school affairs prevented me from contacting them and that my being seized by Xinjiang police was just a fabrication of Xinjiang separation activists.

When I finally called my family, I did not say that I was in Turkey or that Xinjiang separation activists made up a lie about my incarceration. After I got off the phone, the police explained that the lies were intended to make my family feel at ease and that I would benefit from complying with their instructions. They instructed me to contact my family again using Skype. They listened in while I spoke to them. When my family asked me where I was, I gave them an indirect answer. They were unsatisfied.

On September 12, I was moved to the Fulihua Hotel(富丽华大酒店). I was again put on 24-hour surveillance. The police allowed me to call my school in Turkey to explain why I was absent. They wanted me to tell the administration that I was staying in Xinjiang because my mother was sick. I, of course, wanted to tell them the truth. As it turned out, I was unable to connect with the administration, but I was able to speak to a teacher. The police had a Turkish speaker listen in on our conversation. They did not allow me to say anything about being seized by the police.

In exchange for my cooperation, the police allowed me to contact my roommate in Turkey so that he could help me register for the fall courses at the Turkish university as I was unable to do this using the Internet in China. They let me use the Internet to contact him, but when I tried to open my email account, I found that someone had changed my password, so I had to create a new account. These efforts turned out to be in vain because I missed the deadline for registration.

By October, there was still no evidence of release or possibility of being able to go back to school. So I wrote a letter expressing my impatience to an official. On the morning of September 29, the police chief came and told me I could go back home on the 30th and that I could go to Istanbul around the 8th of October, but I never saw the police chief again. I just remained in the hotel room, isolated.

In the afternoon of the 30th, I was visited by a commander who was very emphatic about my avoiding contact with my girlfriend and Iham Tohti.

The day finally came. It was October 1. They brought me my wallet, cell phone, and other things, but not my Turkish language proficiency certificate, Turkish residency permit, flash drive, SIM card, PC, or passport. They said those items would be kept in storage. In addition, I was forced to take their 1000 RMB. They gave me a new SIM card and the number of the person who would pick me up when I arrived in Hotan. My flight to Hotan landed around 6 pm that day. On the way home, one of the two officers confiscated my ID card as per the request of the police chief in Urumqi.

During my 79-day enforced disappearance, I lived in a state of constant torment. I was unable to contact my family to let them know of my whereabouts. All communication with the outside world was severed. My mother had a heart condition that I could know nothing about. I couldn’t talk to anyone, not even during Ramadan.

However, more than 2 months passed after I was sent home and I got nothing back from the police. They all have been refusing to answer my phone calls or online letters. Without ID card or passport, I could not leave my hometown, not to say going back Turkey to continue my master study in Istanbul University.

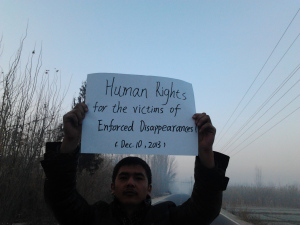

On International Human Rights Day, I strongly demand human rights for all the victims of enforced disappearances, including me.

Mutellip Imin

December 10, 2013

(Contact me via mutellipimin@gmail.com or Skype:mutellipimin)